A 45-year-old woman arrived in our office in significant pain. The day before, she had seen a dentist for a painful lower left central incisor. The recommendation was straightforward: extract the tooth and then see a periodontist.

She refused. Instead, she searched for another option and drove nearly 50 miles to our office.

The Clinical Picture

She was hitting tooth #24 every time she closed her mouth—and it hurt badly. The gingival tissue was visibly swollen, and the tooth had Class III mobility.

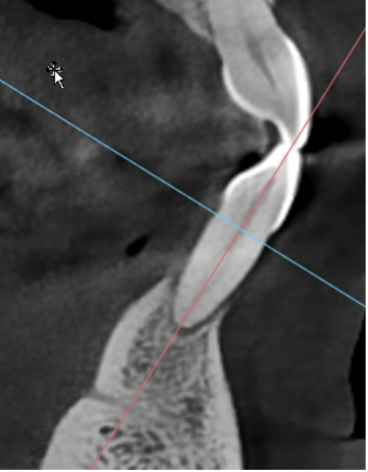

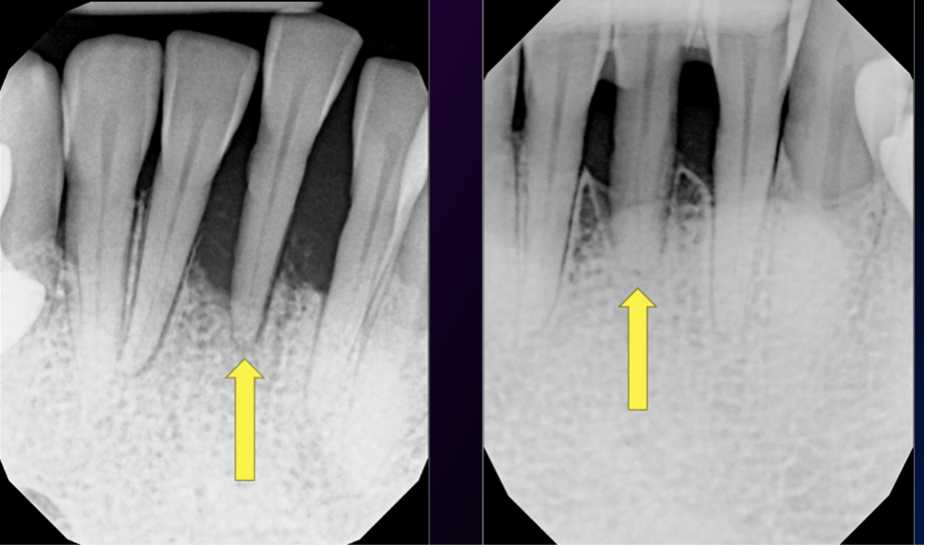

Radiographs showed severe bone loss. At first glance, this looked like a tooth destined for extraction.

But something didn’t fit.

What Didn’t Add Up

When we probed the rest of the mouth, we found deep pockets elsewhere—like a 9 mm pocket on the distal of tooth #4—with surprisingly little calculus.

This wasn’t typical chronic periodontitis.

This was aggressive periodontal disease, where the probe drops apically with almost no resistance and minimal calculus is present.

That distinction matters.

First Visit: Stabilize, Don’t Extract

The patient was anxious and in pain. Probing around #24 wasn’t possible.

So we did three simple things:

- Careful local anesthesia—inject a drop of local in the vestibule. Wait for a minute. Then inject through the numb spot. Patients love it.

- Occlusal adjustment—we reduced the incisal edge so she stopped traumatizing the tooth.

- Diagnostic testing

The relief was immediate once the tooth was taken out of traumatic occlusion.

Diagnostic Testing

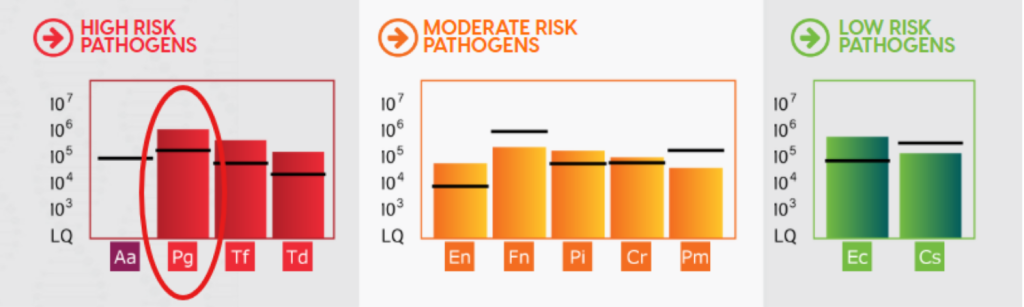

We collected a microbial sample and ran a MyPerioPath test from OralDNA Labs.

Testing matters because dentistry should work more like medicine: identify the pathogens first, then treat.

OralDNA doesn’t just identify periodontal pathogens—it also helps guide antibiotic selection, rather than relying on guesswork.

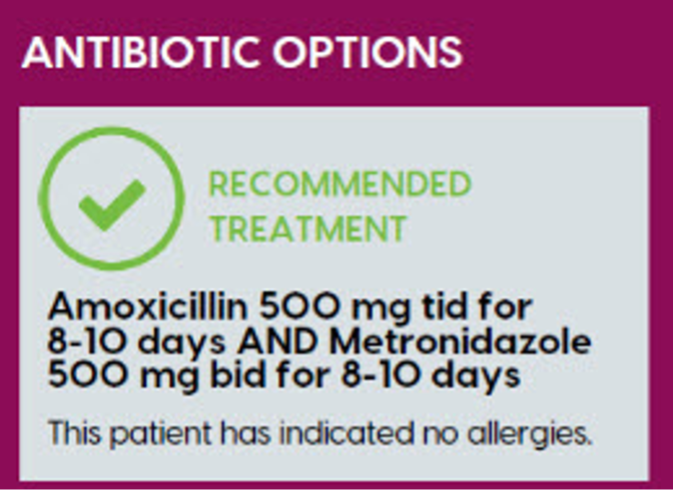

Because this patient had a severe active infection, we started empiric antibiotics (amoxicillin and metronidazole) immediately while awaiting results.

Five Days Later

The tissue had already settled down.

My son, Dr. Matt Sheldon, splinted tooth #24 (to #23 and #25), but she was feeling better even before the splint was placed. Infection control—not extraction—was already changing the outcome.

Definitive Treatment

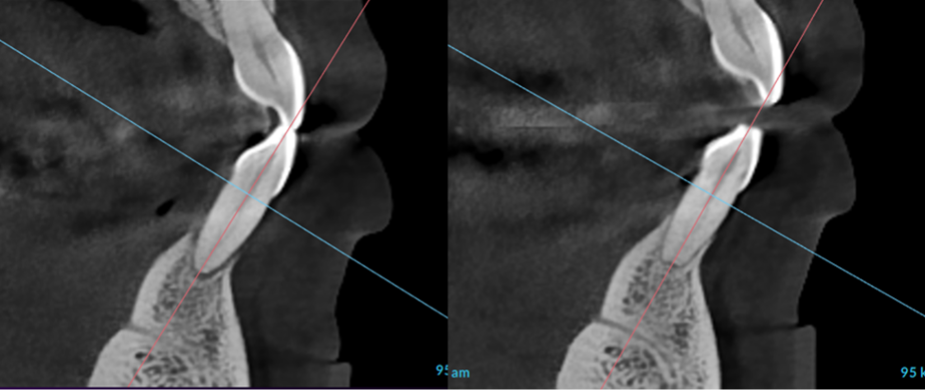

Next came periodontal endoscopy, allowing us to go beneath the gumline and ensure the root surfaces were truly clean.

Next came periodontal endoscopy, allowing us to go beneath the gumline and ensure the root surfaces were truly clean.

Weeks later, pocket depths had dramatically improved—nearly all were resolved.

The Proof Is in the Bone

Look at tooth #24. Bone regenerated.

This wasn’t magic. It was the result of:

-

- Removing traumatic occlusion

- Identifying the bacterial profile

- Using appropriate antibiotics

- Thorough root debridement under direct visualization

The Takeaway

Patients can heal—even teeth that look hopeless—when we diagnose properly before we treat.

Several months later, the patient returned to the office. Not because of a problem. She came in to give me a hug. And honestly, there’s no better outcome than that.

Clinical Pearl

When severe bone loss presents with minimal calculus, think aggressive periodontal infection—not mechanical failure.

Stabilize occlusion, identify the pathogens, and treat the biology first. Extraction should be the last decision, not the first. To see this case in detail as well as patient resources, go to LeeSheldonLectures.com

- When a “Hopeless” Tooth Isn’t Hopeless - January 23, 2026

- Do We Really Need Antibiotics for Periodontal Disease? - September 5, 2025

- Saving Teeth, Avoiding Implants: Dr. Lee Sheldon’s Strategic Approach to Aggressive Periodontitis - June 20, 2025